Before we publish the results of part two of our IPA blind tasting, our Resident Beer Scholar, Chris Brady, returns with another of his journeys back in time. Here, he goes back to the earliest days of the India pale ale styles, busts a few myths and finishes up back in the present day, where hop heavy IPAs are becoming ten a penny.

Most craft beer drinkers will be familiar with India Pale Ale (IPA), the moderately strong, hoppy and bitter pale ale. This much is unarguable.

Many will also be familiar with the oft repeated history of the style: back in the days of the British Raj, around the turn of the 19th century, the British troops in India were thirsty. To remedy this, the industrious brewers of old England shipped over their weak beer (for all British beer is weak) only for it to arrive after many months at sea in a foul and noxious state. So our inventive brewers fixed the problem by making the beer more alcoholic – and adding more hops – as both constituents are known for their antimicrobial power.

Thus India Pale Ale was born, a beer invented to solve an export problem.

Delve a little deeper, however, and more specifics attach themselves to this narrative. It turns out that IPA was invented by a Mr George Hodgson at his East London brewery; that his beer was designed to be much stronger and hoppier than other beers of the time; that this design enabled it to survive the long sea voyage to India whereas other beers arrived spoiled; that IPA was immeasurably improved by the sea voyage; and that this new IPA was much beloved by the British troops.

Unfortunately, if you keep digging, you’ll discover that none of this is strictly true. Esteemed beer historians such as Martyn Cornell and Ron Pattison, along with others, have combed the archives and reported that these long-accepted facts are merely myths built upon a foundation of truth. So let’s go myth-busting!

Hodgson didn’t invent IPA

What is true is that Hodgson did indeed export beer to India and was the first to acquire fame and acclaim for doing so. However, he wasn’t the first to do so and he didn’t create a special beer for this purpose.

Records show that unspecified “beer” was being exported to India as early as 1711, well before Hodgson’s time. Towards the end of the 18th century, more detailed records show that a huge variety of goods was being shipped to India including hams, cheeses, pickles, ceramics, perfumes and fabrics.

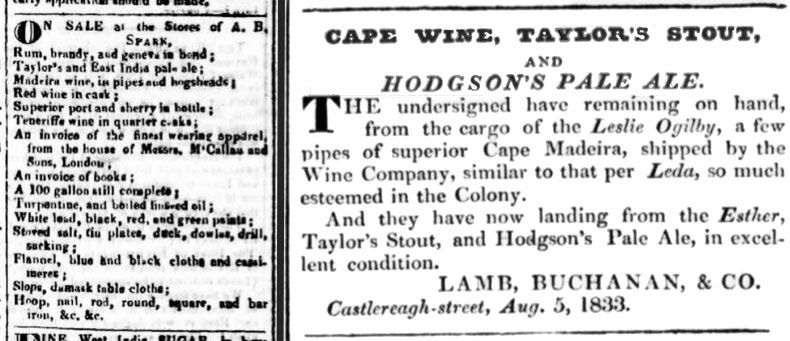

Alcoholic drinks were also shipped: wine, madeira, sherry, cider, and beer. Advertisements from the time show that a number of brewers were sending a wide variety of styles to India, and indeed around the world. Porter, stout, small ale, table beer, Burton ale and pale ale were all successfully shipped to the East Indies. Some of these styles are familiar while others only exist as fading print in dusty shipping records.

Hodgson’s initial success didn’t even have much to do with the quality of his beers – as real estate agents are prone to say it was location, location, location. In the early days of exporting to India, many products were shipped privately by British officers and captains of the East India Company. Shipping goods to India was inexpensive as most of the demand for freight was coming back to the UK, so this little trade in treats from home was a nice little money spinner for British on their way out to India.

These private exporters weren’t too fussy about which brewery they sourced their stock from and so Hodgson’s brewery at Bow, being very close to London Bridge where India-bound ships set sail, was ideally placed to capitalise on this demand. The fact that Hodgson gave his customers long terms of credit helped Hodgson’s Brewery become the go-to supplier for many individuals exporting beers.

Towards the end of the 1700s, branded pale ales were advertised for sale in publications such as the Calcutta Gazette. Hodgson was one such brand but other breweries had also got in on the act.

It’s important to note here that the pales ales were not called IPA or indeed trumpeted as being any different from the pale ales pouring in the alehouses and taverns of London. In fact, the term IPA (AKA East India Pale Ale and India Pale Ale) didn’t come into use until the first half of the 19th century, at least 50 years after pale ales started being specifically named on shipping records and export advertisements, and at least a century after beer had first been shipped. And, even then, it was very likely a supplier’s rather than a brewer’s term.

Interestingly, one of the first times the name East India Pale Ale crops up seems to be from Australia, in the Sydney Gazette, on August 29, 1829. However, the only thing new about the beer was the name.

IPA was probably made with extra hops

By the latter years of the 18th century brewers understood the preservative power of the hop and would use an increased amount for any beer – not just pale ale – destined for ageing or export. However, the history books are decidedly sketchy on what exactly was the difference between a domestic pale ale and a pale ale destined for export. What we do know is that sometime in the early 18th century, at least 100 years after beer was first exported to India, brewers and export / import professionals began advertising pale ales as being “prepared for the Indian market", often referencing its suitability for the Indian climate and the British constitution.

In the latter years of the British Raj "prepared" almost certainly meant "more hops". But even this is no argument for the IPA invention story as it is clear that porter, stout and cider (no hops at all!) were all being shipped to India as early as the early 18th century and this export continued for a good couple of centuries.

IPA was higher in alcohol to enable it to arrive in good condition

Brewing records show the pale ales which eventually became known as pale ales prepared for India, which in turn came to be called (East) India Pale Ales were not, in fact, particularly strong for the time. Most were around the 6.5 percent ABV mark, which was comparable to the porters of the time and considerably weaker than double stouts that were around the 9 percent mark.

There was also an almost forgotten style, the Burton Ale, a precursor to latter day barley wines, that had first been shipped to Russia in the 17th century and weighed in at around 10 percent ABV. All four were being shipped to the subcontinent, which makes the case for a IPA being specifically designed to be stronger start to look very flimsy indeed.

IPA was possibly improved by shipping, though perhaps not by today’s standards

Another idea that’s been the subject of no small amount of conjecture is the assertion that IPA was somehow improved by the sea voyage. What we do know is that prolonged exposure to heat will artificially age a beer, accelerating the oxidative processes that lend beer the classic flavour characteristics associated with age.

Before the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the voyage was around four months long and involved crossing the equator twice whilst getting around Africa. This would certainly equate (pun intended) to a much longer period spent at cellar temperature. If we assume that aged pale ale was desirous and that ale shipped to India arrived prematurely aged, then we can logically assume that this journey would be perceived by by consumers as having improved the beer.

This is still conjecture though. All we know for sure is that there was a demand for beer in India and recipients would wax lyrical over the qualities of pale ales.

British troops didn’t necessarily drink IPA

For centuries beer was brown, due to brown malt being produced using a smoky and hard-to-control heat source such as a wood fire. It is true that pale malt, and therefore pale beer, was possible via small scale sun-drying of germinated barley, but in grey old England it wasn’t until the advent of coke in the latter years of the 17th century that British maltsters were able to produce pale malt in large quantities.

The "new" pale beers were initially more expensive to make than brown beers due to the new technologies involved and, as such, the early converts were the landed gentry who’d have pale beers made in their private breweries. Pale beers thus became something of a status symbol associated, and desired, by the upper echelons of society.

Conversely, the cheaper brown beers, which eventually morphed into porters, became the drink of the working classes. This class divide of beer styles was mirrored in the colonies with the aspirational pale ales drunk by middle class civil servants and upper class commanding officers. Though some soldiers would have undoubtedly had pale ale, the majority of the rank and file troops mostly drank brown porters as their fathers had done before them.

So what did historical IPA taste like?

Historians have gleaned several pertinent clues from contemporary literature but this still leaves us with a somewhat incomplete picture that invites a certain amount of conjecture based on present day brewing science.

In 1840, a London physician, Dr William Prout, opined that, in his professional opinion, not all ales were equally good for his convalescing patients, writing:

“Some of the finer kinds of Burton ale, however, are unobjectionable; particularly those prepared for the Indian market, which are not only carefully fermented, so as to be quite dry, or free from saccharine matter; but they also contain double the usual proportion of hops.”

Another clue comes from 1841, when the famous Burton upon Trent brewer, Bass, ran an ad in The Times that described their East India Pale Ale as being:

“…more perfectly fermented, and approaches nearly the character of a dry wine; it has the light body of a wine combined with the fragrance and subdued bitter of the most delicate hop…”

So we can glean from this that it was a dry beer and this is borne out by brewery logbooks that record very low final gravities.

We know that brewers used 100 percent pale malt so the beer would have been quite pale. We know that, at least by the 1800s, brewers were using more hops for export beers, yet the pale ales of the time were extensively aged even before shipping, which would have tamed the bitterness somewhat as well as negating any hop aroma. Another likelihood is that brewer's yeast wasn’t the only agent of fermentation.

Some writings from British drinkers in India attest to the beer arriving in “sparkling condition” despite the fact that it was common practice for casks intended for export to be de-bunged for a period before shipping in order to degas the beer to reduce the risk of over-pressurised casks rupturing en route. This seems to suggest that a secondary fermentation could occur in transit in an already highly-attenuated beer. A likely culprit is Brettanomyces, a species of wild yeast that can chew on proteins and complex carbohydrates that brewer’s yeast cannot. Brett character may have been a component of the “peculiarly fine flavour” that at least one 18th century commentator attested to.

In short, despite the idea of a barrel-aged Brett IPA being so hip right now, historical IPAs didn’t have too much in common with modern English IPAs, let alone the fruit salad sensoramas of contemporary craft IPAs.

Decline of IPA

By the late 1800s, the glory days of IPA were numbered. The British were to leave India in 1947 and, by the early 1900s, domestically at least, the cheaper mild ales were massively popular, with the relatively expensive wood aged IPAs being out of reach for the huge numbers of working class people.

The two World Wars, with their interrupted international trading, rations and higher taxes, both dealt IPA a severe blow. Gravities and therefore ABVs tumbled so there was no longer much to differentiate it from ordinary 3 to 4 percent ABV bitters. It was no longer the drink it once was.

America

The US had been a lucrative market for 18th and 19th century British brewers, and barrel-aged IPAs were also brewed domestically in the English style. However, the Prohibition years from 1920 to 1933 put paid to that with most of the smaller IPA producers not surviving the long time between drinks.

The only IPA brewer to survive and thrive after Prohibition was Ballantine, and its IPA – barrel-aged, high ABV – was an anachronism that harked back to IPA’s halcyon days. Ballantine IPA may have survived Prohibition but it could not survive 20th century economics and the trend for light lagers. Ballantine IPA eventually became a portfolio anomaly owned by US megabrewery Pabst and, in 1996, the brand was finally laid to rest.

However, Ballantine IPA inspired a generation of beer drinkers and brewers. Two of the most legendary brewing companies that kickstarted the US craft beer revolution, Anchor Brewing and Sierra Nevada, were pioneers of craft beer and their groundbreaking IPAs – Anchor’s Liberty Ale and Sierra Nevada’s Celebration Ale – were directly influenced by the original Ballantine IPA.

The first craft brewers tapped into drinkers’ growing thirst for something different from the omnipresent light lager and the success and growth of craft IPA both in America and here in Australia is intrinsically linked to the emergence of new hop varietals. The Cascade hop was pivotal in the development and success of both Celebration Ale and Liberty Ale. Along with yet more new hops came the boom in craft beer and, in particular, the new American IPAs.

By the late nineties and early noughties double IPAs emerged. Brewers in the San Diego area (Stone, Pizza Port, Ballast Point, Alesmith etc) became so adept at the new supersized IPAs that they became colloquially known as San Diego Pale Ales.

Today, many breweries have an IPA as part of there core range and IPA has split into myriad substyles: double IPA, triple / imperial IPA, Belgian IPA, black IPA, white (Wit) IPA, session IPA. In the midst of this slew of newcomers it is ironic to note that English IPA has seemingly been reduced to a variant.

IPA in Australia

It’s often noted that the Australian craft beer industry is tracking a similar upward trajectory to that of the US, albeit a few years behind. To put this in perspective, it’s worth remembering that, at around the start of the 2000s, when the US market had matured to the extent that IPAs were commonplace and breweries such as Stone and Russian River were breaking new boundaries with style-defining double IPAs, Little Creatures had just opened and was struggling to turn drinkers on to its Pale Ale. Still, IPAs have now become commonplace in Australia’s booming craft beer industry with more than 50 straight IPAs at time of writing available from local brewers in bottle or can (by "straight", we mean no session, double, triple, black, white, red, rye IPAs and so on).

A more recent variant is the Australian IPA, typically operating as a showcase for relatively newly developed Australian hop varieties such as Galaxy, Ella and Vic Secret.

IPA has come such a long way from its origins as an export pale ale that it almost seems ludicrous to try and connect the two. In many ways, IPA as we know it is indeed an invention, but one that occurred in America and some 200 years later than most would assume.

As for the historical proto-IPA, I’ll leave the last words to a real beer scholar, Martyn Cornell:

"IPA – no evidence of an actual inventor, no evidence of an actual invention."

You can read other Drinking In Style articles by Chris here.

We'll publish the results of part II of our IPA blind tasting tomorrow; in the meantime, you can see how part I unfolded a few weeks ago.