Australia might be a major exporter of raw barley and malt, but the number of maltsters operating on our shores is relatively few. Yet, as the local beer scene has grown, so too has the number of people producing malt with the country's small breweries in mind.

One of the newest additions to Australia’s nascent craft maltster fraternity is Ballarat’s House of Malt. It's headed by Drew Graham and, although the first bags of malt have only just started rolling out of his factory, it’s an idea that's been years in the making.

“The reason I got into malt in the first place was, during my science degree at university, I fell in love with brewing and realised that’s where I wanted to go,” he says.

While becoming a brewer might have seemed a logical first port of call, instead it was landing a job at Joe White Maltings in Adelaide that brought Drew into brewing’s more agricultural – and arguably less sexy – side.

Eventually, his career brought him to Ballarat, a regional city Drew felt was the perfect fit for a new small-scale malting operation. The original home of Joe White, Ballarat has much to offer such an enterprise, from the scores of nearby barley farms to its proximity to Melbourne and the growing number of local breweries.

“One of the issues with our consumer society is how far things need to come,” Drew says. “Going back to having things local – which is how it use to be – is a really important movement and I want to be a part of it.”

All of House of Malt’s barley comes from within 100km of Ballarat and Drew’s plan is to send what he makes no further than Melbourne.

“It’s such a big industry and things are normally done on such a big scale,” Drew says. “The amount of malt I can put through in a year is about the size of some maltster’s batch sizes.”

The process of making malt is one we’ve covered in the past, most recently in a piece by Molly Rose Brewing founder Nic Sandery. For Drew, each step of that process – the steeping, the floor malting and the kilning – is something he does alone, armed with little more than a wheelbarrow to move grains throughout a system he designed himself.

It’s a setup specifically tailored to produce malt for small brewers, with the decision to opt for floor malting one that sets Drew apart from the vast majority of maltsters. Rather than relying on automated machines to move his barley and create his malt, Drew turns his across the floor of his germination chamber (or, as he likes to call it, the Chamber of Malt) at least every 12 hours over four to five days. With a rake more typically used to make sure concrete dries evenly, he shifts the barley as it germinates to make sure the temperature remains at an ideal level.

“You want the depth of the bed somewhere between 150 and 250 millimetres; the thicker it is, the more heat it will develop, and the thinner it is, the less heat it will develop,” he says.

“At the start of germination, it won’t generate that much heat but, the longer it goes, the more heat it will develop. So, for the first day of germination, I’ll turn it twice a day and, by the end, I’ll turn it three times a day.”

Floor malting a process practiced by few today. Cryer Malt imports floor malted varieties from Weyermann in Germany and Thomas Fawcett in the UK and Melbourne based BeerCo has just started bringing in floor malted Maris Otter from England’s Crisp but, locally, it was only Launceston’s Not For Horses using such techniques in recent years. And, since founder Bill Armstrong moved to 3 Ravens to become a brewer (where he still creates nano-batches for some of the brewery’s beers), his custom designed setup has moved to Van Dieman’s farm where it awaits full reanimation.

As for varieties, Westminster and Latrobe are the main barley varieties Drew's been working with, although he stresses the importance of being flexible. Working closely with local farmers means constantly considering each yield and how the barley looks once it’s harvested.

“The problem with barley is it’s very dependent on the season," he says. "What happens during the season can affect how well the grain might malt.”

Drew is advising brewers to treat House of Malt’s first release, an Australian ale malt, like the UK’s Maris Otter, a malt that once fell out of favour with England’s industrial brewers, remained popular in real ale and homebrew circles and eventually rose to prominence once more.

“The idea is that it’s a backbone malt with plenty of flavour,” Drew says.

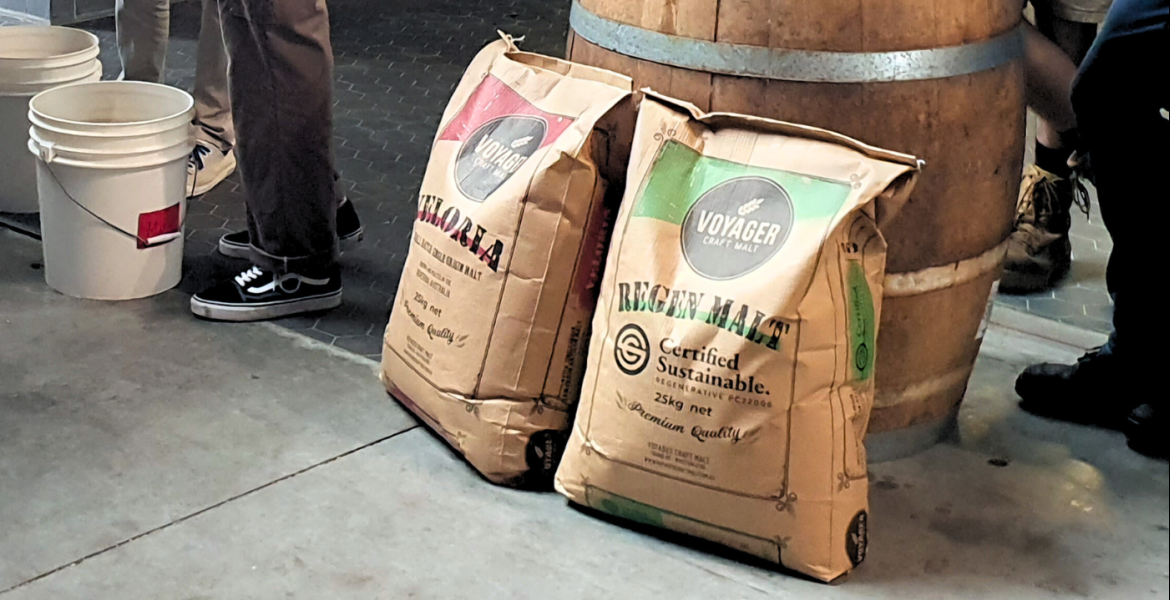

Despite the inherent inefficiency that comes with being a small maltster, just as many craft breweries have successfully capitalised on their points of difference from big beer, Drew believes there are distinct advantages in his operation’s size. For one, like other small Australian malt producers like Voyager Craft Malt in NSW, it means he can work with breweries to design malts for specific beers.

“If someone wants me to tailor a malt for what they want to achieve, or if a brewer had barley they’d grown they wanted malted, I’ll be offering that service,” he says.

“I want to be able to cater for brewers who come to me, who want speciality beer, and provide them with an option.”

Find out more about House of Malt here and check out other entries in our Collaborators series here.

If you are part of or know of a business that we might like to feature in the series, get in touch.