The past few decades have seen the Australian beer scene transform from monochromatic to kaleidoscopic. As some point, each of us has had our eyes opened to the sheer variety of beers available: the different styles, different colours, different flavours. But this vast array of drinking options isn’t all that gives the beer industry its rich texture. The people we have to thank for producing our beloved brews are as diverse as the beers they make.

As an industry that celebrates innovation, creativity, camaraderie and, let’s face it, good times, it’s one that’s drawn in all-comers from all manner of backgrounds. Sure, it’s hard work making a living off brewing beer, but when you’re bringing joy to people it beats working hard to make a living in pretty much any other way.

The presence of so many colourful characters within the local beer world has helped it become what it is: as they infuse their own breweries, bars and festivals with their personalities, it all adds to the greater whole – creating a place that couldn’t be further away from the homogenous lager-lager-lager days of yore.

Two such characters hail from two of the cornerstone breweries of Sydney’s inner west: Glenn Wignall, co-founder of The Grifter Brewing Company, and Oscar McMahon, co-founder of Young Henrys. Their backgrounds resonate with each other and show remarkable parallels at certain junctures, yet their lives and personalities are distinct.

Glenn’s quiet, steady voice almost belies his adrenaline-fuelled skateboarding years, but lends weight to the life lessons and business wisdom he’s drawn from his experiences. As for Oscar, the 14 years he spent in a hard rock band have left him with a spark of excitement behind his eyes – he’s quick to laugh, and uses what’s come before to fuel where he’s going next.

Glenn Wignall

Glenn hails from New Zealand, where he started skateboarding in an Auckland cul-de-sac around the age of seven. When he entered his teenage years, he got serious, and immersed himself in skate culture, spending every spare minute either on his board, filming and photographing skaters, or working in a skate shop. In 2005, now 21, Glenn and a couple of mates took a two-week skate trip to Sydney that resulted in them moving there permanently.

And this is where Glenn’s beer discovery began: tasting his way through the Australian beers that were different to the brands back home, he discovered Coopers Pale Ale, and his interest was piqued by terms like “bottle-conditioned” and “active yeast”. A homebrew kit and a few bartender jobs followed, starting him on his journey towards brewer.

But this whole time skateboarding had never left his life. He’d spend his free time hitting the streets and the skate parks at every chance he got, exploring untouched areas of Sydney and even landing sponsorships to skate for overseas brands. As the years ticked by, the filming and editing he’d taught himself while skateboarding led Glenn to study digital media and get a job in television. When he decided that skateboarding wasn’t going to be his main gig, he swapped his overseas sponsorship for a local one and became good mates with Trent Evans, the owner of the Australian skate brand that sponsored him.

The next while saw Glenn double-down on homebrewing, his other passion, which led to him becoming mates with Trent’s homebrewing flatmate, Matt King. He joined a beer club and a homebrew share club, brewed a beer for Trent’s skate brand, and, along with Trent and Matt, decided to have a crack at brewing larger batches of beer under the Grifter moniker.

That was 2012, with the trio invited to make use of spare tank space at a small new brewery in Newtown called Young Henrys.

Oscar McMahon

From the day he started at Newtown High School of the Performing Arts, the grit, graffiti and good times of Newtown got into Oscar’s blood; in his words: “It was fucken punk and it was loud and it was grimy and pretty gnarly.”

Like Glenn, Oscar skated the streets of Sydney, found a taste for better beer, and coincidentally also studied at the Enmore Design Centre (though the two didn’t meet until years later). But, while skateboarding remained central for Glenn, Oscar’s driving force was music. He and a few friends who were also into punk rock and metal got together to start a band, and the Hell City Glamours were born.

Like most things in life worth anything, the band was hard work. Rehearsals and gigs and recording were all squeezed in around a bunch of different jobs to pay the rent. Hell City released a few EPs and two albums, toured Australia a number of times, and even embarked on an American tour following the release of their second album, supporting the likes of Alice Cooper and the Angels. But, upon returning from the US, after 14 years of working hard and playing hard, the Glamours decided to call it a day.

While working in a bar, Oscar befriended a local brewer, Richard Adamson. Oscar’s creative side started flirting with beer, and it quickly became the object of his affection. At a time when good beer still had to be hunted down, Oscar and Rich started Beer Club, a monthly gathering of people who were crackling with excitement about trying new beers. And, inevitably one night, those fateful words came from Rich’s lips: “How good would it be to start a company to get all kinds of people this excited about beer?”

With the same passion and hard work he’d poured into music, Oscar joined Rich to grow Young Henrys from that seed. Just like another trio of dreamers, in fact…

Fast forward to the present day, and Oscar and Glenn are both running successful breweries in Sydney’s inner west (Grifter even bought Young Henrys old brewery before expanding again), and both see the ongoing influence of their former lives in their companies today.

Mick Wust sat down with Oscar and Glenn to talk beer, business, backgrounds, and brand identity.

You guys both started your breweries around the same time. What do you think about the Sydney beer scene, then versus now?

Glenn Wignall: In regard to our breweries, I often say that I feel like we’re still the babies in the beer game, but when you stop and think about it, we’ve been around for a lot longer than a lot of other guys around, which is wild. I guess that’s a sign of how quickly things are progressing.

Oscar McMahon: If you think about the first time that you and I met, was at Beer Club… craft beer was this thing that was exciting, but there was no easy access. If you think about the people who were in that Beer Club then – Steve [Blick] from Stone & Wood, we’ve got three or four staff who were in it, some Grifter boys, a bunch of other people that have entered the beer industry for a time and left – it was that time of people getting excited and trying to find craft beer.

GW: A beer event was rare back then. And now it feels like there’s stuff on every week. Not saying that’s a bad thing.

We used to go to these homebrew share things at the Local Taphouse [now The Taphouse]. I used to look forward to that for the whole three months in between times. Bunch of guys that would go too that have their own breweries or brewing companies, like Doctor’s Orders, and Shenanigans guys were there… Pete from Wayward was always there…

OM: I remember when we started, there were 180 breweries in Australia. There’s now 550-plus. And with that there are so many positives, but also it’s hard to find people with beer educations, ‘cause they’ve done their own things. The Ballarat uni course only accepts 30 people a year.

GW: When the TAFE one came out, I heard a lot of people trying to go for it couldn’t get in.

OM: Something I think was great about Sydney’s timing is that the small bar scene and the craft beer scene all started kicking off in a similar timeframe.

GW: I remember that era as well – bars were opening up every second week, ‘cause they changed licensing and made a small bar definition. I definitely reckon that helped.

You could appeal to a smaller market. You didn’t have to appeal to everyone.

OM: That’s right. I think that’s part of what’s exciting about craft beer. You don’t need to make a product that’s mass acceptance. We know that our total market share as craft is, what are we at, eight percent of total beer? Not even? So what would our little percentage of that be? You can kinda do what you wanna do and you know you’ll please someone.

GW: I remember talking with you a few years ago, about craft beer definitions and all that

crap, and you were saying it’d be good if we could just be referred to as “beer”. There’s “not very good beer”, and then there’s “good beer”, and if you pay any attention to who made it you’ll no doubt see that a lot of it comes from smaller, independent brewers.

I think it’s almost like that now, and craft brewers are making beer for all types of drinking occasions, not just extremely hoppy or weird styles.

OM: There is definitely a sector of people who, instead of just being immersed in it and enjoying it and that being a positive experience, get negative on things that don’t meet their expectation.

“As soon as Pirate Life sold, the quality of their beer went down…”

No, it didn’t! They still make excellent beers. It’s like: “They’re not punk rock any more…” But craft beer is a process.

GW: I think those negative people are caring more about where it came from than what it is.

Both of your breweries have a strong brand identity. How did you go about building that, and holding onto it as your businesses have grown?

GW: It’s a fine line for anything that grows. It’s gotta be done at a certain pace; you can’t grow too quickly. I know core values can be lost along the way.

OM: I think core values are the most important thing. And, speaking from our experience, you can’t control growth. When that shit starts rolling, you haven’t effected that. You can fuck it up…

GW: That’s why having core values in the first place is a good idea. When things don’t go right, you can come back to them: “Does this meet these values?”

OM: When you’re at that fork in the road, got to decide A or B…

GW: New things are always popping up all the time. We have to stop and think: “Do we want this?What do we want?”

If you don’t stop and have those discussions about how to navigate, you go blind, and could end up doing things you’re not happy with.

OM: It’s a tricky thing to navigate. You have to make decisions not just based on financial outcome. Asking: “Do I actually think this is cool?” ‘cause some of the things we as Young Henrys have said no to, it’s because someone said: “We wanna do this!” but I don’t care that we’d make a lot of money out of it, I don’t fucken believe in it.

If you have the rare chance of being able to own and run a business that you believe in, the moment you do something you don’t believe in, you lose that. It’s this weird other type of currency which is unspoken.

If you give up your values in the business, you lose that currency.

OM: Exactly. The only people who really realise that value are us. You can’t do an Instagram post saying: “We just said no to this today." No, the stuff you say no to, you say no to very respectfully: “Thanks, but it’s just not right for us at this point in time.”

And learning to say no is probably the most important thing.

GW: I’ve finally got the opportunity to do something that I can pour all my passion into that wasn’t skating, ‘cause I reached a point where I knew it wasn’t going somewhere. Now I’ve got something that’s going somewhere, and you get to do all that creativity… it ticks a lot of the boxes that skateboarding did, but in another industry, and it has its own culture, and scene, and you get to be part of a community…

OM: I use you guys as an example quite often when asked about breweries that have a good strong identity and sense of self. You guys have always known what your brand looks like, what your business is. What you say yes to, and what you say no to. You’re a really good case in brand, and brand identity, and having the beers to match.

So, from the outside, you look at Grifter, and think that’s a well rounded business. It has an identity, a whole bunch of owner-operators who know that identity and protect it, and their brand is influenced by the people that they are, and the beer is a reflection of those people’s tastes. That’s a good business right there.

GW: I reckon both breweries highlight the importance of the people involved, and the backgrounds they come from. And walk a good line between beer, and drawing influences from outside beer culture. Which I think is good for us, and I would say has been the same for Young Henrys. Music is obviously a huge focus for those guys, with Oscar, and Richard coming from a musical background as well.

OM: And our logistics manager has won an ARIA! How funny’s that?

What do you mean when you say “draw influences from outside beer culture”?

GW: We don’t collaborate that much with other brewers. That’s not ‘cause we don’t like other breweries, but because we like to collaborate with a customer, or a restaurant, something a bit different. That’s more appealing to me.

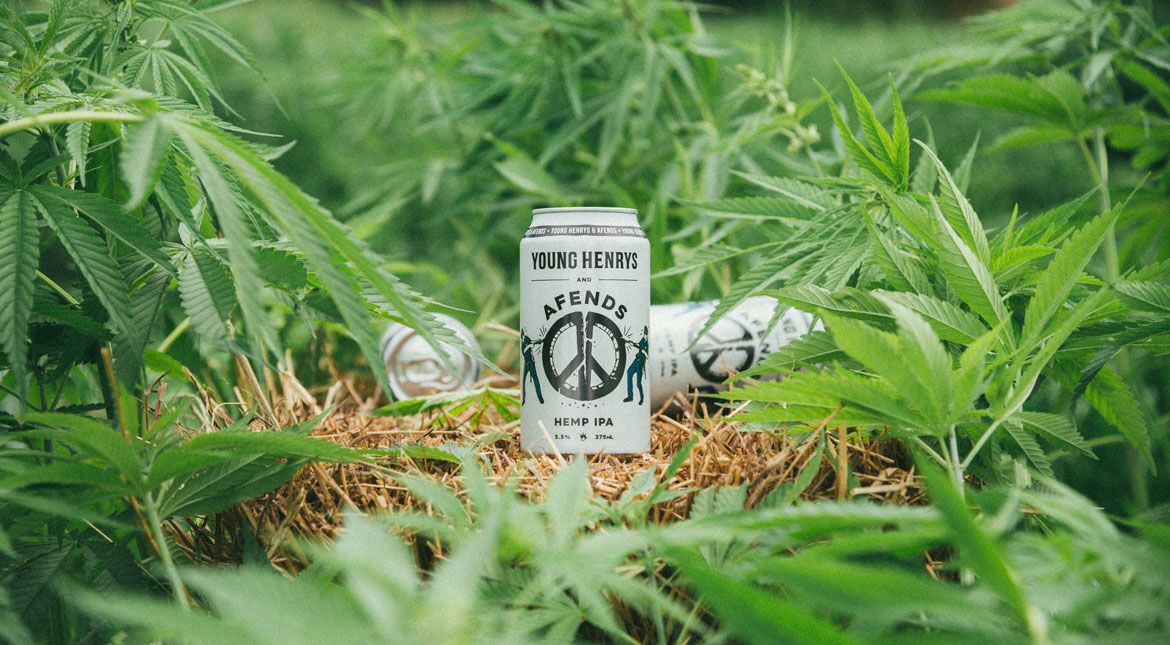

OM: That’s an interesting point. We’ve always tried to collaborate with people more outside of beer as well. We’ve always thought it’s more interesting.

If we were to do a beer with Grifter, for example, two breweries making a beer together, it’s very expected, we’re probably only going to be talking to people in beer already. But if we do a beer with a band, the band is going to be super psyched on it, and that energy feeds into you.

You have to come up with something creative. Like working with a chef, you have to come up with something that’s going to fit their audience, their taste, their palate. You have to come up with a design that makes both entities excited. And when it comes out, you’re adding value, and talking about beer to their audience. And those people may never have had a conversation about beer before.

And that’s how good beer spreads – through new people finding it through things like that. That’s how we’ve always really enjoyed doing… but we’re not against anyone who wants to make beers with other breweries by any stretch.

GW: I have done collaboration beers with other brewers and have found it to be very beneficial, but more so on a technical level. More benefit to the brewers themselves, by learning techniques, what’s their solution for the same problems we face.

OM: I reckon probably all of the inter-brewery collaborations that have happened over the last seven years, which is my experience, is how the quality of our industry has risen so much. Every time you do a collaboration beer, even with a band, we learn something. They’ll say something like: “This is our objective, this is what we want to achieve” and seeing how they position and market themselves to their audience, I think: “Wow, you guys aren’t four drongos, you’re actually a music marketing company… that happens to be called a band.”

Or collaborate with a chef, and see how someone with a refined palate approaches flavour.

How do your backgrounds from skating and music influence your businesses? I’ve met plenty of brewers who come from a science or engineering background, but what flavour does skateboarding and punk rock bring to a brewery?

OM: One of the things that skateboarding and music lends to someone is that you are completely aware the whole time that you are part of a counter culture. You become really comfortable standing out, or being different, or doing your own thing. And that’s a lot of what the craft beer industry’s about. It is a counter culture, to mainstream beer culture. People in the craft beer industry don’t have to please everybody, like people at a metal festival aren’t trying to please everybody.

Being in a band is not dissimilar to running a business, in that it’s more about the harmony of the people in it and being creative together and having the drive to do it… that’s the important part of business. The cool thing about being in a band is that you rarely have the opportunity to make a decision based on finance! You just make decisions based on: “Do I wanna do that? Yeah, it sounds cool, let’s do that.”

GW: We don’t push the skateboard thing by any means, but we always pay homage to skateboarding. We support skateboard events and stuff like that and sometimes even have things at the brewery. Some of them we probably wouldn’t do again, like ramps and whatnot…

I learned a lot of good things from skateboarding that help me in brewing as well. Skating’s not a team sport – you’ve only got yourself to motivate you. So you’re out by yourself, trying to do something or learn something. You learn pretty quickly that you’ll get there in the end, but it’ll take a long time… and with that comes some sort of sacrifice but if you apply yourself you’ll get there. I look at what I’ve done with the brewery and I attribute a lot of that to skateboarding.

Being sponsored to skate, and being paid to play music, and owning a brewery are all perceived as being “dream jobs” where you get paid to do your hobby, but a lot of people don’t realise how much hard work they involve. How do you balance the hard work, and the stress, with that “best job in the world” expectation?

OM: It’s a funny thing, that idea of perception. I’m really proud of how hard we’ve worked and where we’ve gotten our company to. And anyone that says: “You’re killing it, you’re so lucky”, it’s like, nah, fuck that, don’t discredit the work that we’ve put into it.

And also, we work for ourselves, and that does not mean knocking off at two and getting on the beers. That means we work. It means we don’t pay ourselves as much… even if I was doing my job for another craft beer company, I’d be getting paid more than I am working just for ourselves. That’s just the way it is.

When we open a business and that goes well, it’s because you love it and believe in it. It’s not about the money you’re able to put into your bank accounts. It’s about the people involved. It’s about the emotion and drive you’re able to put into your business. Because that’s what makes a business go well. It’s you being committed to it, believing in it, and setting that ethos.

GW: I get a sense that some people think anyone who makes beer just turns water into money, which is definitely not the case! It’s not easy out there. But I don’t believe in playing the “poor me” card, and you shouldn’t flaunt successes too much either. Sort of just fly under the radar.

I try not to think about that sort of thing too much; just focus on doing the best we can with what we have. I didn’t have a fancy job to begin with, so I’m used to doing grunt work. I like being down on the street level, dealing with other small businesses, so I don’t find it too hard.

Just stay humble, I suppose.

OM: Stay as humble as you can as long as you can.

See Glenn grinding rails and smashing pales in this “Best of” clip and Oscar with the Hell City Glamours in this film clip.