From popping bottles and exploding cans to beers turning dark through oxidation or arriving at venues uncarbonated, there have been plenty of examples of beers leaving local breweries not quite right in the past year or so.

Sure, when there are thousands of new, often experimental beers being released each year and millions more litres being produced by the country's smaller brewers than at any stage in the past, there's more opportunity for something to go awry. But, with more craft beer consumers and greater coverage of the scene than ever before, it's arguably never been more important to ensure such things don't happen.

From a brewery business perspective, at a time when competition has never been fiercer, who wants to be known as the brewer of dodgy beer, whether it's occasional, one-off or otherwise? And, when the country's independent brewers are preparing to ramp up their efforts to persuade drinkers to #askforindiebeer, such an ask only gets tougher if indie beer isn't also good beer; you can be sure the former independents that are now part of global operations – Mountain Goat, 4 Pines, Pirate Life, Feral and Green Beacon – will be putting out consistent, quality beer.

It’s why you'll hear the message around quality hammered home repeatedly at events like BrewCon, why there's a growing body of resources at hand for brewers wanting to learn more, and why you'll find more brewery owners investing in quality management programs, whether in terms of technology, knowledge or both.

“Quality is important if you want people to drink your beer again,” says Dan McCulloch (pictured below).

As technical manager for Lallemand Brewing, he spends his time travelling throughout Asia Pacific helping breweries establish quality management programs and addressing problems they might be encountering in production.

“For a brewery producing core range beers, quality is critical because people want that beer to be the same every time – it’s about consistency," he says.

“But even if a brewery’s focus is small batches of different beers every time, quality is still important – otherwise people won’t come back to try the next weird and wacky thing they are doing.”

What Is Quality Management?

Essentially, quality management can be broken down into two areas: quality assurance is planning and putting in place the processes along every step of production to ensure the consumer receives a quality product within the brewery’s specifications for that beer; quality control is about monitoring and checking to ensure all of a brewery’s operations and activities fulfil the quality requirements that have been put in place.

Achieving consistency to a high level involves many factors too, from raw materials and stringent production processes through to good sanitisation.

“Quality is a whole team mindset," Dan says. "It is about managing the entire process and this has to come from the top first.

“Breweries need to have standard operating procedures and ensure that everyone involved in the production process does things the same way — from brewing through to packaging. If one person does something a little differently that batch could be different to the previous one … or ruined completely.”

He says the industry has come a long way from the days in which off flavours such as diacetyl and acetaldehyde were common, but in their place are new frequently found faults.

"What I am noticing are what we call house flavours, or 'house geschmack'," he says. "Breweries that taste their own beers daily is great, and [is something that] should be done during their daily gravity checks, but they can become desensitised over time to things such as chlorophenol, which is antiseptic or band-aid like.

"It's a taint from chlorine in water I'm tasting in many beers and can be for two reasons: the carbon filter to remove the precursor chlorine hasn’t been changed and is no longer working, or the brewery is brewing more – which is great – but the contact time with the carbon is not enough due to the amount of water now going through it and the housing needs to be upgraded. So, as the brewery gets bigger, the flavour creeps up, and they don’t notice until someone else comes in and tastes their beers.

"The other flavour is residual caustic and this usually knocks off the hop aroma and adds a soapy residue to the beer – and this is of a great concern."

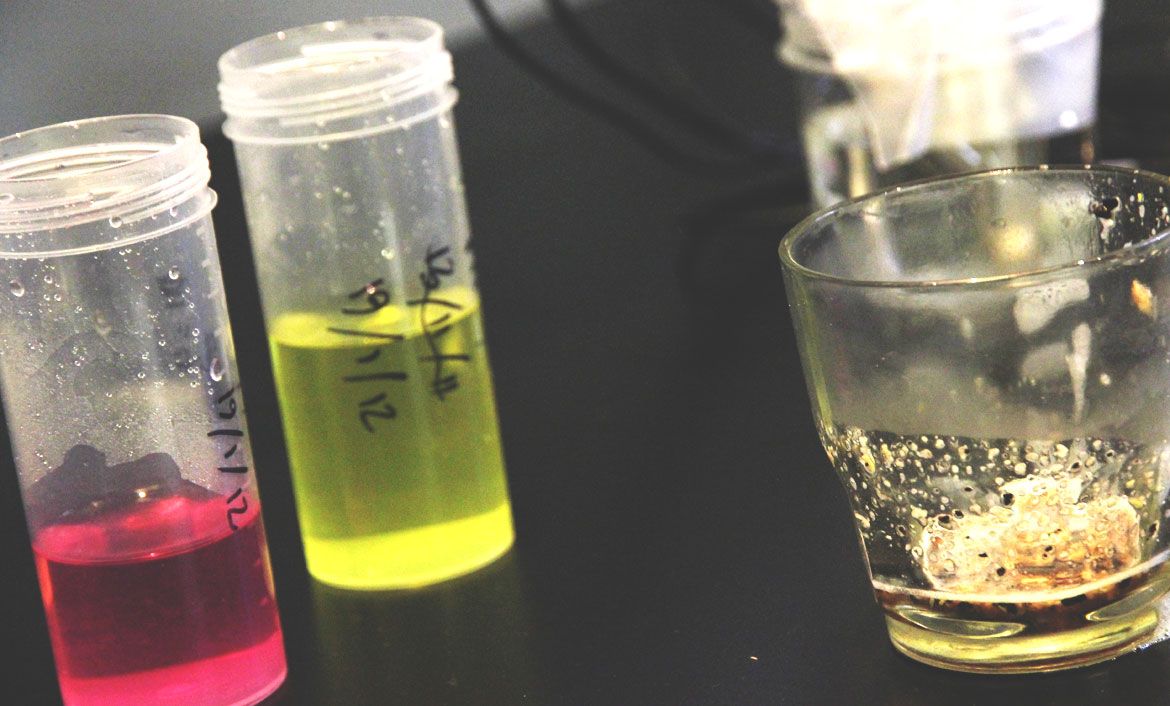

A basic lab setup and simple training can help overcome such a situation and assisting breweries with the creation of labs is one area of focus for Dan.

“A lot of people are scared by the thought of establishing a lab because it sounds like you need to be a chemist or a microbiologist … you don’t,” he says.

What's more, brewers can set up a basic lab on a very small budget then build complexity as the brewery grows. In doing so, they have a better chance of picking up on many of the common faults still plaguing the industry: oxidation, flavour taints, bacterial infections. They can occur all too easily, so having the capacity to recognise them and determine what went wrong is key to a brewery’s quality control.

Why Does It Matter?

As one of Australia’s largest independent brewers, Gage Roads have a quality team larger than most. Clare Clouting leads a three-person team at the West Australian brewery: her role is quality assurance manager; alongside her are a quality coordinator and a quality officer.

“Some of the practices will be very similar, no matter the size of the brewery,” Clare says, explaining that, ultimately, "my job is to make sure the consumer is happy.”

For a brewery like Gage Roads that’s focused first and foremost on a core range, she says the number one priority is to make sure their beer always tastes exactly how it should: the brewery’s top-seller, Single Fin, always has to taste like Single Fin.

“A lot of what we’re doing is cost avoidance, protecting your reputation and protecting the consumer,” Clare says.

Unlike many smaller brewers, Gage Roads pasteurise their beers; it's a word that can send shivers down the spine of some craft beer brewers and drinkers who view the process as one that negatively affects the taste of a beer. But, in Gage Roads' case, as a brewery that sends beer across the country and is stocked in major retailers, the aim is to apply a limited amount of pasteurisation for beer stability.

“People need to know if they’re going to drop $60 on a carton then it’s not going to have undergone a secondary ferment or be sour,” Clare says.

“Single Fin is a really good example, because for us that’s become a beer people buy as their regular weekly carton. So, we’ve got all these consumers who really know what Single Fin tastes like and the moment it tastes slightly different they’re emailing me very quickly.”

While she admits smaller breweries who can sell their beer quickly and close to their brewery might not need to worry about pasteurisation, those sending their beer across the country should consider it. That said, there is plenty of work that can be done earlier in the process too.

“We don’t apply a whole lot of pasteurisation because what we try to do is work on all the stuff at the front end,” Clare says. “Clean ferments and brewing under the best possible circumstances, so we can give it the minimum pasteurization we can get away with.”

BIRA QUALITY

Clare (pictured above) is also a founding member of the Brewing Interlaboratory Reference Analytes, or BIRA for short. The not-for-profit group was formed off the back of the brewers’ conference in 2017, when some quality-focused minds, including Dan, came together and decided to help breweries ensure their quality testing practices were up to scratch.

“We wanted it to be affordable for really small breweries because we feel that if we can help everyone raise the level of their quality testing then we can help everybody,” Clare says. “Craft beer is all in it together and it’s all of our reputations as a whole."

By sending sample beers to breweries to be tested, BIRA are able to provide feedback on how accurate a brewery's testing processes are. Then, if and when quality assurance practices go awry, they're on hand to help find a solution.

“If they do something wrong, then it might be an operator not following the procedure or equipment might not be right and then we will help them troubleshoot what the problem is,” Clare says.

“If you’re going to spend a lot of money or time on testing then you want it to be accurate. So, we’re helping people drive the improvement in their quality testing.”

Dan says it's important for brewers to remember quality control doesn’t end with production and packaging – it extends to distribution and sales.

“Sales representatives should be tasting the beer in venue to make sure there are no issues – such as dirty lines affecting a beer,” he says.

“It’s about breweries educating the publican to dispense the beer clean as well. The consumer is getting smarter and, as we get more craft breweries, quality is fundamental because quality beer is what is going to last.

“That’s where a quality management program comes in – breweries should have a quality program from day one.”

Case Studies

So, what steps can brewery owners take to give themselves the best chance of nailing quality and consistency within their budgets? What should they consider when working out what's most important for a brewery of their size?

Below we look at examples of large, medium and small breweries with reputations for making consistently high quality beers to see how they operate. Before we get to that point, however, Dan suggests a range of simple quality checks that every brewery should be undertaking:

- Monitoring and tracking fermentation curves and forced fermentations.

- Having a "release sheet" for each beer before it is packaged that includes specifications (gravity, ABV and pH levels), detailed tasting notes, and an overall score. This information needs to be logged into a database for future reference so that trends can be monitored.

- Testing yeast health.

- Testing water quality.

- Keeping samples of every beer batch and tasting them at regular intervals – for example, every three months – so the brewery can see how their beer is ageing in a typical consumer environment (in other words, not in a cool room). Again, this information needs to be entered into a database.

- Undertaking simple microbiological tests for bacterial infections and/or sending samples to an external lab for testing.

And, he adds: "Never be afraid to dump a batch of beer if you think quality isn't there. In the long run, it's the best solution to re-brew.

"In the stress of the moment, it might not seem like it, but if you're not 100 percent happy, would your customer be?"

Large: Gage Roads

At Gage Roads, the brewery’s size, distribution network and the fact they contract brew are all factors that mean their food safety requirements are far reaching.

“It’s pretty comprehensive,” Clare says. “We do make Woolworths products and products for other people … so we have to be accredited to the Woolworths standard, which is pretty robust, and we also have HACCP accreditation.”

Clare says much of the brewery’s quality assurance takes place well before brew day starts, with the right ingredients, packaging and systems all affecting quality, particularly given the size of the brewhouse.

“Once we commit to doing a pilot brew, it’s quite a lot of money for us if it doesn’t work out,” she says.

Along with the three-person quality team, Gage have invested heavily in their laboratory equipment. But Clare says that while their alkaliser, which measures the alcohol level in beer, or their CBox, which measures Co2 and O2, might have been significant costs, they are built to last.

“If you were to set up a lab to the scale we’re running, if you were to do it right from scratch, it would be about $150,000 to $200,000. But we did build ours over time,” she says.

“If you make good investments and look after your products and treat them well and keep them clean, then they will look after you in the long term. Most of our pieces of equipment predate my joining Gage [the alkaliser is nearly a decade old], we will have had them five to ten years and they’re still going strong.”

What's more, the cost of letting bad beer get into drinker’s hands can be far greater than the cost of a crucial piece of equipment.

“You do your risk assessment and, if the cost of all the beer in one tank is going to be $30,000, then you might dump that and that would have paid for your oxygen analyser.”

But, no matter how good your equipment and extensive your setup, there’s always a human element to ensuring beer quality.

“We taste along most steps; we taste at the end of ferment and the bright beer stage – sometimes in between depending on what’s going on," she says. "We taste the finished products and we do shelf-life tasting.”

Clare also runs a lot of blind tastings, which includes picking up Gage Roads' own beer from bottleshops to test against similar beers in the same style.

“It’s good for us to understand how our consumer is drinking our beer; a lot of the time we’re drinking fresh beer and it spoils us a bit,” she says. “I think it’s important for brewers to understand what the consumer is getting and how it appears to them – particularly if it’s sat in someone’s bottleshop in the middle of summer for two months.”

For sensory training they involve staff from across the brewing and packaging teams and, while they frequently train staff to detect faults, detecting specific faults isn’t essential.

“We stick to what’s true to type, so even if a person can’t exactly say what they think the problem is, we still take down all sorts of notes."

And, while Gage Roads might have a bigger quality team and more gear than many of their peers, there’s also more risk: more beer being sent to more places and more staff means more room for human error; and the bigger breweries get, the more there is to keep clean, bringing sodium hydroxide – or caustic – into play.

“It’s a risk for every single brewery but the bigger and more complicated the brewery is, the bigger the risks become,” Clare says.

“We have lots of checks in place. We always check the pH and alcohol of the first product that comes off the line and that tells us what’s in that first bottle is what it’s meant to be; it’s not being watered down or somehow got caustic in it.”

Medium: Hawkers

The morning ritual in the laboratory at Hawkers is a sensory analysis session with four or five staff from all areas of the brewery’s operations – not just those directly involved in brewing.

“We get everyone participating in the sensory analysis because it’s about educating everyone in the brewery,” says senior technical brewer Alex Lovelock.

The sensory session involves looking at the appearance, aroma and taste of a selection of up to ten beers that have just been packaged as well as older retention product to see how it is holding up over time periods of up to 12 months. The panel has no idea of the age of each beer and scores are entered into a comprehensive database.

“We are all quite familiar with what the beers are and how they should look, smell and taste and this is where having four or five people doing the sensory analysis becomes important,” he says.

After four years Hawkers has brewed more than 950 batches of beer – both their own and for others – and information on every batch is captured in the company’s database – what Alex calls "the heart of our quality control program".

Analysis of packaged beer is only one part of the sensory process, with the brewing team conducting sensory analysis at the end of fermentation (both before and after dry-hopping) and from the bright beer tank. The most important test during production is for diacetyl – a by-product of yeast fermentation (often described as buttery or butterscotch like) that is produced naturally by fermenting yeast and then reabsorbed at the end of fermentation.

“The sensory data gets transferred to our fermentation sheets and the final analysis goes into our database for each individual beer that we make,” Alex says. “We are looking for any faults in the beer and from the results we can address any production issues we may have and make improvements to our processes.”

There's a host of other tests conducted prior to and during production, such as those for equipment hygiene, wort stability, water quality, gravity, alcohol volume and bitterness.

Quality control also extends to packaging (where the biggest threat is oxygen pick-up), storage and distribution. Hawkers hold samples of each batch for a year; all packaged beers are date stamped and a sample is taken from the packaging line every hour so, if there is an issue, it can be isolated.

Quality management has developed as the business has expanded from four staff to 50, from what Alex describes as “very basic minimal analysis” in the early days to a full quality management program. Today, there is a dedicated laboratory on site in the Melbourne suburb of Reservoir, with three cellar/laboratory staff working specifically on quality control – although Alex, like Dan, is quick to point out that quality is a whole team approach.

“The more you are brewing the bigger the consequences if things fail,” he says. “So it’s all about continuous improvement."

The company continues to invest in more advanced laboratory equipment – such as $40,000 on an updated dissolved oxygen and CO2 meter – and in late 2018 employed pharmacist Melinda Foulkes to enhance the technical skills in the lab.

“It was a big step up to get a brewing chemist on board,” Alex says. “But, as you are producing more and more volume, you need specialists in different areas.”

Hawkers also use external suppliers, sending samples to Symbio Laboratories twice a week for microbiological testing.

“The craft beer market has matured in the last three or four years – people are more educated and a lot more choosy because there is variety," Alex says. “If you start putting out product that is not meeting expectations or is inconsistent then you will lose customers.”

Small: Whitelakes Brewing

The brewery team at Whitelakes, located in Balvidis south of Perth, numbers just two so you won't find the same level of equipment or resources as at Gage Roads or Hawkers. At this stage, however, they don’t package and, as a result, head brewer Sean Symons says their QA program can be streamlined.

“We keep things very simple," he says. "We do very basic micro, we do quality and taste analysis, and a measurement of alcohol. We don’t get much more complicated than that because we just need to guarantee the product is going to last 12 weeks – which isn’t a great hurdle in draught beer – and we’re comfortable that we can deliver on that promise.

“When you start putting it into package, and you’re looking at much longer shelf life, then that becomes a little trickier."

While they invested in a dissolved oxygen and CO2 meter – and Sean's brewery design features a few non-standard bells and whistles – the rest of their lab is made up of a good microscope and a gravity meter to check their ABV.

“We’re nuts and bolts brewers, so with a microscope and a little bit of nous you can do not quantitative analysis, but qualitative stuff,” Sean says.

“We employ a microscope to do basic cell counts and yeasts counts to make sure our yeast pitching and management is as good as it can be. We do a lot of lagers and they’re delicate little beasts, so yeast management is a key part of making sure you can deliver on a craft lager from batch to batch.”

Sean says breweries that send their beers out into the world in cans and bottles, however, should be aware of the need for a substantial increase in lab and quality equipment. Before launching Whitelakes, Sean spent more than two decades working for breweries big and small, including a period at Swan Brewery prior to its closure by Lion in 2012.

“At Swan we had blokes with 40 years’ experience doing the same job day, in day out, with all the procedures, all the written manuals and all of the accreditations under the sun,” he says. “Every year we’d still budget for something to go wrong. Even with all that stuff in place, we still had something up our sleeves because we knew there would be something we wouldn’t foresee happening.

“For a smaller packing line where people aren’t doing the job every day or it’s mobile, where someone else is operating it, well, it’s fraught with danger. So, everything you can do to mitigate that risk is really important.”

When it comes to allocating your limited resources, he believes breweries should focus on what’s most essential.

“It’s often a really tricky calculation, because the equipment is expensive," he says. "Then how far do you go to give your brewery the protection it needs and the quality the product deserves out in the marketplace?

“If you’ve got an expensive bit of machinery and are only using it once a week then it’s not really making your money work for you.

“The primary objective is to keep the product as the brewer intended; it’s about how much money do you throw at that to maintain a shelf life that the consumer is going to understand and be happy to pay for?”

Will Ziebell also contributed to this article.

You can find other entries in our long-running Big Issues series, ranging from sexism in the beer industry to labeling and from IP to managing consumption, here.

And, if you're reading this in time and heading to BrewCon 2019 in Melbourne, you'll find Dan presenting in the Bintani Room at 11.30am on September 5 and Clare in the IBA Trade Hub at 1.15pm on September 4 and on a panel discussing Managing Quality Of Product Outside Of The Brewhouse in the Cryer Malt Room at 11am on September 5. Full program here.