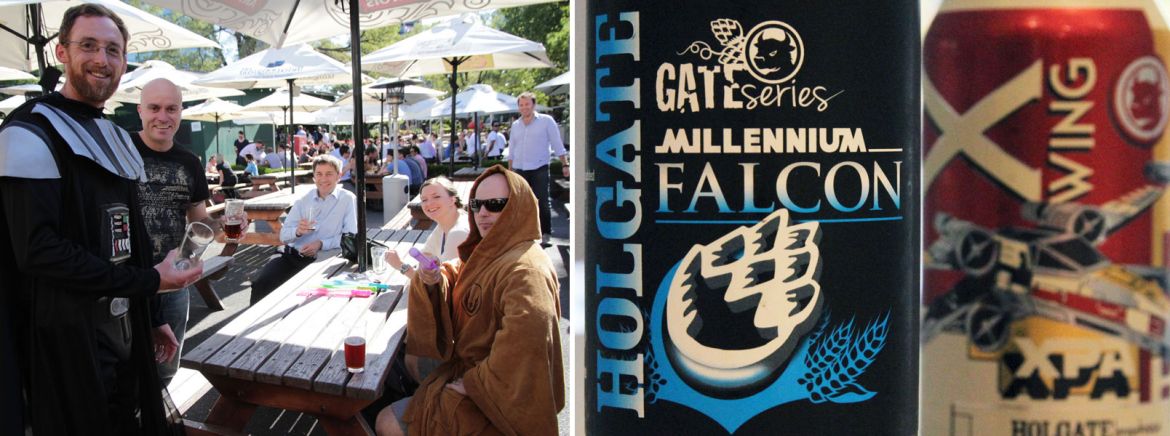

When it comes to naming beers, brewers are a sucker for puns and pop culture references. Whether it's Mountain Goat’s Pulped Fiction, Westy Kong, Lime Crisis or Rye Fighter, the Bounty Hunter Brewing range or myriad local releases that have taken inspiration from Star Wars – Hop Nation’s Jedi Juice, Holgate’s Millennium Falcon “Empirial IPA” and X-Wing XPA, Australian Brewery’s Revenge Of The Pith among them – you don’t have to look far to find examples.

It extends beyond movies, games and television shows too, with confectionary an area that's proving fertile ground for inspiration: Clare Valley and Dainton recently released a Cherry Gripe porter*, with the latter also creating Skittlebrau for GABS; Hack has just released a Crunchy Porter; Cheeky Monkey has offered its own spin on both Frosty Fruits and Ribena; Big Shed Brewing Concern has plenty of fans for its Golden Stout Time and 2018 GABS People's Choice winner Boozy Fruit; and, well, you get the message.

Increasingly, the posting of images of such releases online has drawn attention from within the beer world, with commenters wondering whether some brewery at some point is going to attract the ire of the owners of the original products. In April this year, Sony launched a law suit against US brewer Knee Deep in relation to the brewery's Breaking Bud IPA, which riffs on both the name and title sequence of the Breaking Bad TV series.

The company is not just demanding Knee Deep stop using the name but is seeking damages too, claiming, among other things, the beer was an “obvious effort to trade on the fame and recognition” of Breaking Bad and that the “unauthorized use” of Sony’s trademarks and design elements threatened to erode the value of Sony’s ability to license official Breaking Bad products.

The case is ongoing and, with America’s intellectual property laws different from Australia’s, you can't draw direct inferences as to what could follow here but, with this fondness for referencing well known products and brands on beers showing no sign of waning, should local brewers be worried?

One of the best known examples is Hop Nation’s New England IPA Jedi Juice; the beer debuted at GABS 2017 features both a tattooed Princess Leia and the outline of Yoda’s head on its cans and has gone on to become one of the Footscray brewery’s bestsellers, landing a top ten spot in this year's Hottest 100 Aussie Craft Beers.

Hop Nation co-founder Sam Hambour (pictured above cracking a Jedi Juice at the Footscray brewery) says he didn’t initially think too much about the connection to the film franchise because the beer was named after a strain of marijuana.

“It had some good feedback at GABS so we decided to make it again, but [it meant] we needed a decal because it was going into kegs and pubs,” he says.

“When we launched it [at the brewery], without even advertising it there were two people who came dressed up: one as Princess Leia and one as Luke. I just went, ‘Woah! This is a can of worms that’s been opened right here.’.”

While Sam understands such references can help a beer stand out in an increasingly crowded marketplace, he believes the beer’s ongoing popularity has more to do with the success of the NEIPA style and the fact theirs is a good example.

“I think there is some novelty pop culture factor initially but, from our point of view, the fact that it’s stayed around and has continued to be popular is down to the brewers and the beer,” he says.

“I’m not super proud of the fact that it’s backed onto something that’s not relevant, but I don’t mind too much either.”

As yet, Hop Nation has heard nothing from Lucasfilm or its parent company Disney, but Sam says if they had to change the name of the beer they’d accept it.

“I was always thinking we might get a letter and, if we did, we’d just stop making it,” he says. “It hasn’t come yet, people still want to buy and drink it, so we’ll keep making it.”

The level of concern companies like Disney have regarding such infringements is far from clear and The Crafty Pint was yet to hear back from those contacted for this article (Disney, Village Roadshow Entertainment Group and Netflix) at time of publication.

“I’m sure many of these companies see these hashtags and know what’s happening," says Sam, "and I’d love to hear their discussions in the boardrooms over what to do about it.”

(Fun facts from the 2013 launch photo: Ian "Darth Vader" Morgan is now head brewer at Mountain Goat; next to him is Steve Henderson, formerly of BrewCult; the Jedi is Dan Dainton, now owner of his own trophy-winning brewery.)

But what does the law have to say? Matthew Rimmer is a professor in intellectual property and innovation at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and says a relevant precedent stems from a case involving Lion Nathan and the owners of The Simpsons in 1996.

Lion Nathan (now Lion) released Duff Beer, which Twentieth Century Fox argued people would assume was connected to The Simpsons, given it’s the beer of choice for Homer, Barney Gumble and mates in Springfield. The relevant area of law related to passing off – the notion that companies need to take reasonable steps to ensure it doesn’t appear they or their products are connected to a brand with which they have no relationship. The court agreed with Twentieth Century Fox and found that it was likely customers would assume there was a connection between The Simpsons and Lion Nathan's beer.

“The classic Duff Beer case was really a question of merchandising,” Matthew says. “The courts had recognised that passing off extended to personality rights and, in this matter, they said it extended to fictional personalities.

“I think that precedent would be applicable to craft beer trying to make use of characters or individuals in film and television.”

In Australia, there many aspects to intellectual property, including laws made by courts, copyright requirements, consumer law and international law. Within the Australian beer world, there have been high profile examples of trademark related disputes, as well as others that are ongoing – something we’ll focus on in a future article.

Australia's Copyright Act 1968 sets out what remedies can be sought for copyright infringement. Where an infringement is established, remedies can include an injunction, damages or an account of profits. Damages focus on the loss of income suffered by the copyright owner, while an account of profits looks at the gains made by whoever infringed on the copyright.

Here, copyright is automatically applied in order to protect the rights of content creators and typically remains in place for 70 years after the death of the author (exceptions exist depending on whether the work is published or unpublished and whether or not the author is known). However, fair dealing does allow for some exemptions. Importantly, Australia's system of fair dealing is separate to, and more narrowly defined than, the American legal concept of fair use.

“We have a purpose specific defence of fair dealing, whereas the US has an open-ended defence of fair usage,” Matthew says.

There are only six situations in Australia where you can use copyrighted material without permission and the most common uses of fair dealing involve education, news reporting and reviewing: you can review a movie or report on it by showing short clips, for example, but you cannot host an entire film on your YouTube channel.

Both satire and parody can also be used as a defence of using copyrighted material without permission, provided the use is “fair”. But how a court would view such a defence is unclear; the words “parody” and “satire” are not defined in the Copyright Act and haven’t yet been considered by Australian courts.

“It all depends on the nature of the image you use,” says James Omond, a trademark attorney whose work regularly involves wineries, breweries and distilleries, with clients including likes of Stone & Wood, Holgate, Chivas Regal, Domaine Chandon and various wine industry associations.

“Are you doing a pop culture reference as opposed to taking someone else’s creation and adopting for your own commercial purposes?”

He says guidance around pop culture references on beer labels isn’t entirely clear, particularly if it’s an artist’s interpretation of someone’s work. But he advises businesses to proceed with caution if they plan to head down that path.

“They should think about it very carefully before using this sort of branding because most of the big companies like this will be prepared to take on the little guy and be quite ruthless about how they do it,” James says.

One brewing company that's been having a lot of fun with pop culture is Mountain Goat, with many of the limited releases leaving the Richmond brewery offering more than a nod and a wink to films and games. Tyson Sheean is the man responsible for the design of the labels and decals, including those referenced at the top of the article, and says there's a line you have to be careful not to overstep. In the case of Mountain Goat, he says they look to create puns from the names and are careful not to be too literal with the images.

“There’s always a risk that you are going to go to go too far,” he says. “I’ve never had a letter written to say what I’m doing is wrong, take it down. And, if you do, you just take it down. I don’t want to come across as being irresponsible, but I don’t think you know really until you do it."

For Tyson, referencing movies or games creates the opportunity to tell a story beyond just the label as it gives the brewers the chance to star in videos and have fun.

“It comes back to the beer and the joy of it – brewing it and having fun with it,” he says. “The beauty of the movie genre is it gives you an option of things to play with in a communications sense.”

Nonetheless, Tyson warns not to get too close to whatever you're paying homage to, while also making sure drinkers are in on the joke.

“It has to be in the vernacular or be popular enough," he says. "You can’t be too mysterious with a name. It’s got to resonate but you’ve just got to be careful.”

For Mountain Goat’s Rare Breed and In Breed series, the beers are rarely around for long. When it comes to creating a new core beer, however, Tyson says brewers need to take extra care as the risk of receiving a cease and desist order for a product into which you've invested significant time and effort is far greater.

Were a beer to attract the ire of a large company’s legal team, even if they decided not to seek damages, brewery owners could still be hit with legal fees, the loss of a popular beer or the need to invest time and money into a rebrand and relaunch.

Says James: “If you are going to do this then you need to be prepared at some stage to stop in a hurry. [The] brand equity that you built in your product will be lost to a great extent, but you may be able to leverage that into some publicity.”

As yet, however, we're yet to see a situation like Sony and Knee Deep in the local industry. Legal experts we spoke to for the article suggested companies might not be aware of infringements or might not consider taking action to be worth the time, energy or the associated costs. There’s also the consideration that beers referencing your movie or television show could have a positive effect.

At Hop Nation, Sam says they’ve been careful to keep Jedi Juice on a tight rein, not least because they didn’t want the brewery to be known for a single beer, particularly one in a new style that doesn’t have a clear future.

“Now it’s been a year and a half of Jedi Juice and, in some parts, people would know us as the brewery with Jedi Juice,” he says. “But we don’t pride ourselves on that; we see it as an opportunity to show them the rest of the range and tell our story and open up as many doors on that front.

“Pop culture is fun and good, but I do think it is starting to get pushed a little bit. It does give you an easier sell, there’s no doubt about it, [and] for one-off beers it’s fun and great but, if you want to build a new beer, you want to stay away from it.”

Or, at least, speak to a lawyer.

* The article originally said the beer was called Beery Ripe. This was the name of another similar beer released previously; the Clare Valley/Dainton beer is called Cherry Gripe.