Wollongong is a changing city. Built on the blue collars of smelting and heavy manufacturing, those industries that bought middle class prosperity are in decline, though hardly dead yet; you can still catch a whiff of them each time the open coal carriages roll through town or the smoke stacks of the steelworks begin to wheeze.

But they feel at odds with a newer energy helping power the local economy, one where health is the biggest drawcard and education not far behind – the University is of high repute and it brings youth, vibrancy, multiculturalism and bright minds. If the place is not yet outright progressive, the sensation is bubbling away.

Its attractiveness is not harmed by the region itself being quite beautiful, a thin sliver of civilisation hemmed in by the Tasman Sea to the east and a towering escarpment in the west that contains everything within; golden sand beaches, fertile soil for a small scale agrarian economy, lush bush to wander in and blue sky in which to dive.

Having all this close enough to commute to Sydney means a great many do, lured by the prospect of a life where home ownership and avocado on toast are not mutually exclusive – not yet, at least. With that great southern migration comes the inevitability of gentrification; the cafés, the small bars, the boutiques. Still, things tend to happen at a relatively slower pace here.

By way of example, compare the two cities through the prism of brewing and it’s been the harbour city sprinting away in recent years, with small breweries opening up at a rough rate of one every few weeks. For the best part of a decade Wollongong had a solitary one. But when it got its second, in 2016, it won Best New Brewery at the Sydney Craft Beer Week awards. Yes, amidst all that is good and great in Sydney, they claimed a Wollongong brewery as their favourite. Is that not the ultimate compliment?

The brewery in question was Five Barrel Brewing, which has changed much since – if not in terms of grounded ethos, quality of beer, dedication to supporting local, or those in charge, at least in terms of output and its place in the Gong's beer scene.

The brewery's location hasn't changed either: it still sits in the southern part of Keira Street, in inauspicious industrial surroundings, but has taken over far more of the building it calls home. Where once you'd walk into a small taproom to be faced by a bar straight ahead, now they've opened it up (courtesy of fresh council permission) to reveal the high ceilings, red brick walls, and fermenters that appear tall enough that one could probably have held their entire first six months' output.

There's a food truck installed permanently outside, the bar is a much grander (albeit still far from grandiose) affair, and there's fridges full of cans and merch on offer too. Peer around a corner, however, and you'll spy the original five barrel brewery still in place – now, they just have to work it harder to fill their biggest fermenters.

As the brewery, the venue, and their output has expanded, so has the team – not least with the hiring of brewer Brent Edwards from NZ brewery Good George in 2020 – yet it remains driven by founder Phil O'Shea, with his dad still on hand for shifts behind the bar, of course. No longer do Phil and Mike have to do everything here – brew beer, clean tanks, fill bottles, make deliveries, pour beer, run the bar, write emails, balance the books, and so on – but they do ensure the essence of Five Barrel remains as it always was.

While output has grown significantly since those early days and they put new beers into cans every month, distribution still isn't high on the agenda. They are content – proud, in fact – to be a local brewery, selling as much as they can within the community that in turn supports them most. Sustainability as a business, while retaining sanity and a work-life balance, remains key.

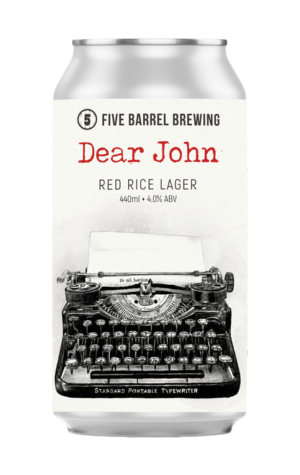

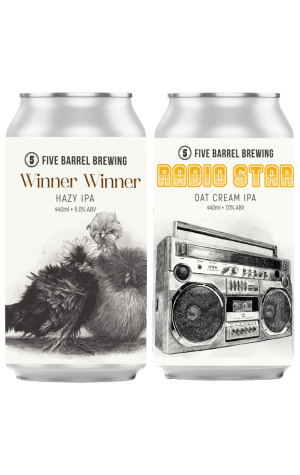

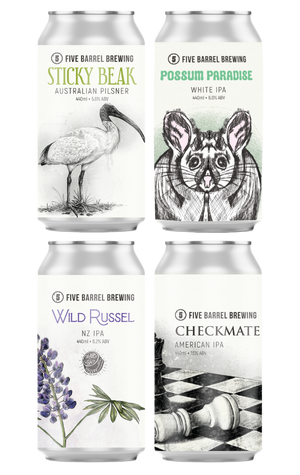

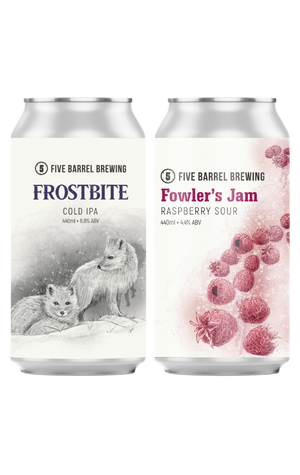

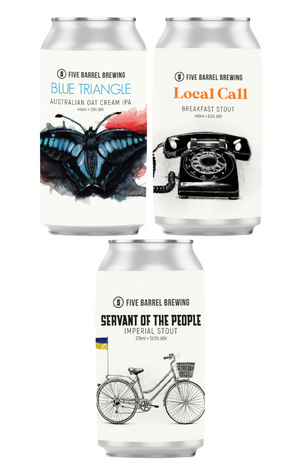

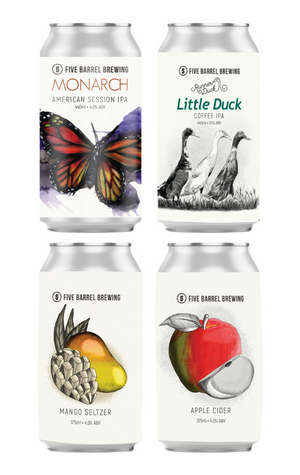

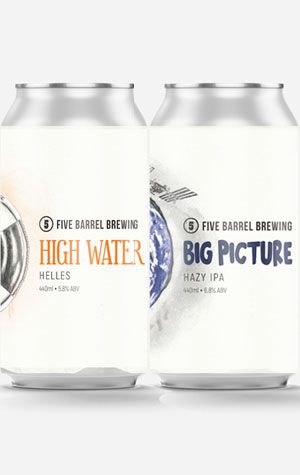

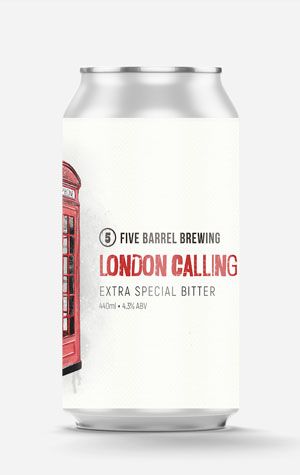

When it comes to beer, if there’s a direction to which the brewery is predisposed it is, you could reasonably argue, towards hoppy beers best drunk fresh. A pale ale and their flagship Hoppy Amber, or Navigator Red IPA as it became following a 2020 rebrand, plus subsequently added XPA and NEIPA represent this in the core range but there’s a perpetual cycle of one-offs and experiments; single hop beers, imperial stouts, quirky sours always worthy of attention. You'll also find artwork from the beers' labels lining the wall as you enter the venue, a neat means of showcasing the frequency of releases and the attention to detail with each.

From very early on Phil has been playing around with barrels in limited quantities – a chardonnay barrel-aged golden ale here, a Flanders style red ale there and a very fine imperial stout each and every year. None of these register highly on the industry hype-o-meter, but all have been splendid.

Sure, the place has changed over time, as inevitably as the city and the people around it will continue to do. But the more important thing is their roots have been firmly planted and they’re prepared for the long haul. They know that any change will be done on their own terms: slowly and incrementally, with local support and without compromising quality or integrity.

In an industry where authenticity is becoming increasingly important, the Five Barrel way feels increasingly like the right way.

Nick Oscilowski